According toLeonard Koren, wabi-sabi can be defined as "the most conspicuous and characteristic feature of traditional Japanese beauty and it occupies roughly the same position in the Japanesepantheonof aesthetic values as do theGreekideals ofbeautyand perfection in the West. Whereas Andrew Juniper notes that "[i]f an object or expression can bring about, within us, a sense of serene melancholy and a spiritual longing, then that object could be said to be wabi-sabi."For Richard Powell, "[w]abi-sabi nurtures all that is authentic by acknowledging three simple realities: nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect. Buddhist authorTaro Golddescribes wabi-sabi as "the wisdom and beauty of imperfection."

The wordswabiandsabido not translate easily.Wabioriginally referred to the loneliness of living in nature, remote from society;sabimeant "chill", "lean" or "withered". Around the 14th century these meanings began to change, taking on more positive connotations.Wabinow connotes rustic simplicity, freshness or quietness, and can be applied to both natural and human-made objects, or understated elegance. It can also refer to quirks and anomalies arising from the process of construction, which add uniqueness and elegance to the object.Sabiis beauty or serenity that comes with age, when the life of the object and its impermanence are evidenced in itspatinaand wear, or in any visible repairs.

After centuries of incorporating artistic and Buddhist influences from China, wabi-sabi eventually evolved into a distinctly Japanese ideal. Over time, the meanings ofwabiandsabishifted to become more lighthearted and hopeful. Around 700 years ago, particularly among the Japanese nobility, understanding emptiness and imperfection was honored as tantamount to the first step tosatori, or enlightenment. In today's Japan, the meaning of wabi-sabi is often condensed to "wisdom in natural simplicity." In art books, it is typically defined as "flawed beauty."

From an engineering or design point of view,wabimay be interpreted as the imperfect quality of any object, due to inevitable limitations in design and construction/manufacture especially with respect to unpredictable or changing usage conditions; thensabicould be interpreted as the aspect of imperfect reliability, or limited mortality of any object, hence the phonological and etymological connection with the Japanese word sabi, to rust. Specifically, although the Japanese kanji characters 錆 (sabi, meaning "rust") and 寂 (sabi, as above) are different, as are their applied meanings, the original spoken word (pre-kanji,yamato-kotoba) is believed to be one and the same.

A good example of this embodiment may be seen in certain styles of Japanese pottery. In theJapaneseteaceremony, the pottery items used are often rustic and simple-looking, e.g.Hagi ware, with shapes that are not quite symmetrical, and colors or textures that appear to emphasize an unrefined or simple style. In fact, it is up to the knowledge and observational ability of the participant to notice and discern the hidden signs of a truly excellent design or glaze (akin to the appearance of a diamond in the rough). This may be interpreted as a kind of wabi-sabi aesthetic, further confirmed by the way the colour of glazed items is known to change over time as hot water is repeatedly poured into them (sabi) and the fact that tea bowls are often deliberately chipped or nicked at the bottom (wabi), which serves as a kind of signature of theHagi-yakistyle.

Wabiandsabiboth suggest sentiments of desolation and solitude. In theMahayana Buddhistview of the universe, these may be viewed as positive characteristics, representing liberation from a material world andtranscendenceto a simpler life. Mahayana philosophy itself, however, warns that genuine understanding cannot be achieved through words or language, so accepting wabi-sabi on nonverbal terms may be the most appropriate approach. Simon Brownnotes that wabi-sabi describes a means whereby students can learn to live life through the senses and better engage in life as it happens, rather than be caught up in unnecessary thoughts. In this sense wabi-sabi is the material representation of Zen Buddhism. The idea is that being surrounded by natural, changing, unique objects helps us connect to our real world and escape potentially stressful distractions.

In one sense wabi-sabi is a training whereby the student of wabi-sabi learns to find the most basic, natural objects interesting, fascinating and beautiful. Fading autumn leaves would be an example. Wabi-sabi can change our perception of the world to the extent that a chip or crack in a vase makes it more interesting and gives the object greater meditative value. Similarly materials that age such as bare wood, paper and fabric become more interesting as they exhibit changes that can be observed over time.[citation needed]

Thewabiandsabiconcepts are religious in origin, but actual usage of the words in Japanese is often quite casual. Thesyncreticnature of Japanese belief systems should be noted.

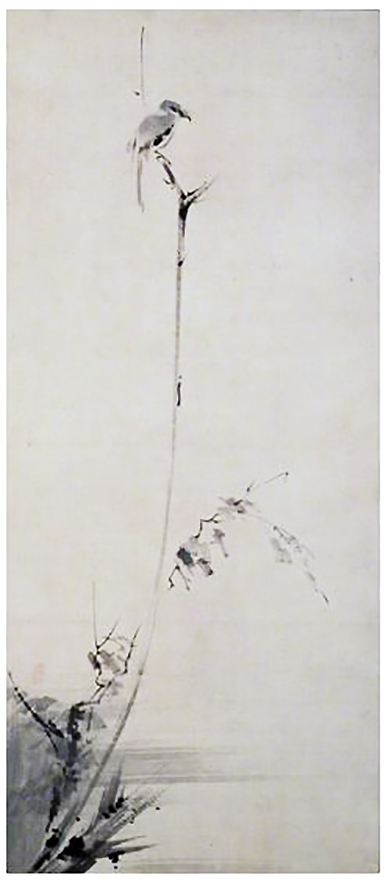

IKI, AWARE

IKI, AWARE

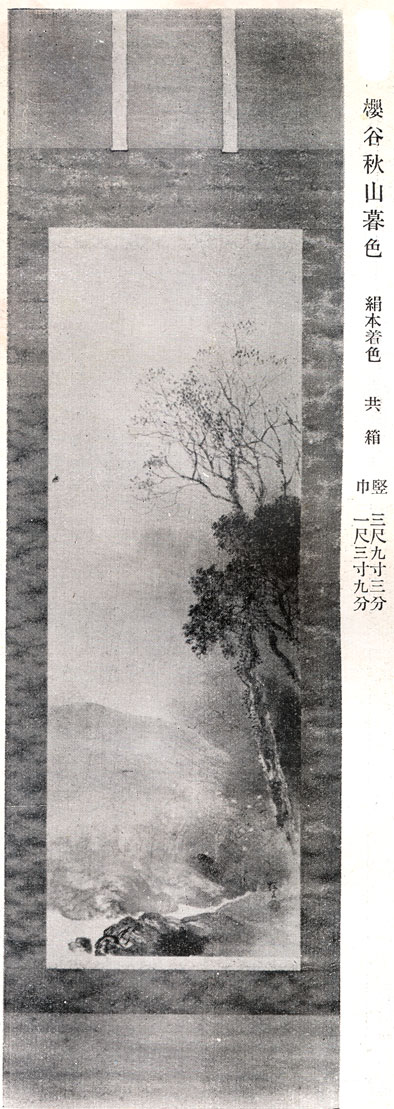

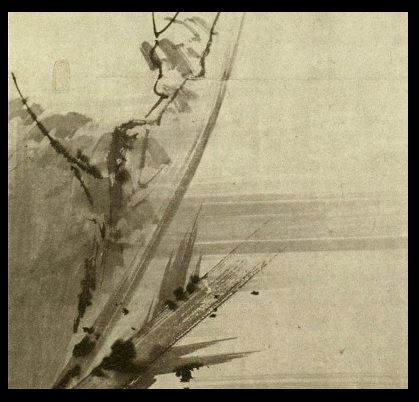

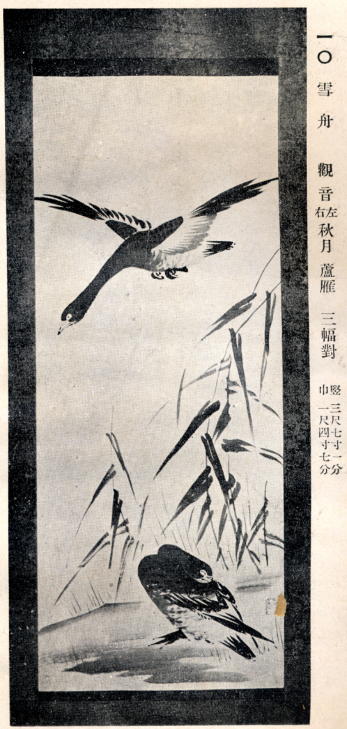

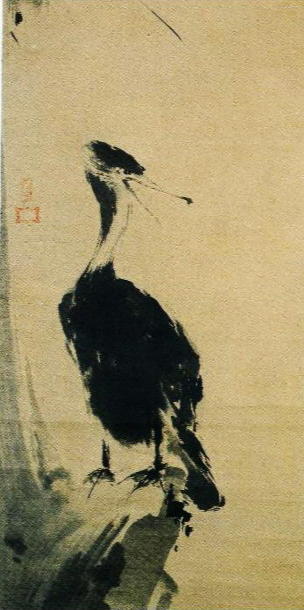

seshuu

seshuu

seshuu

seshuu

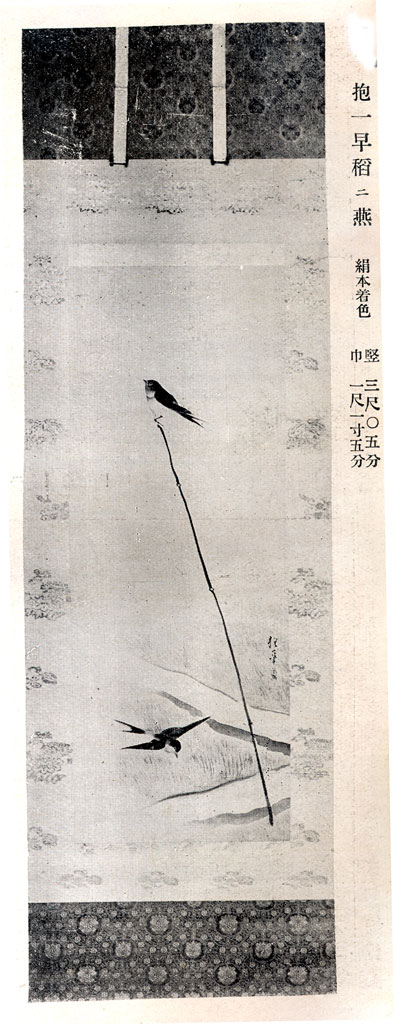

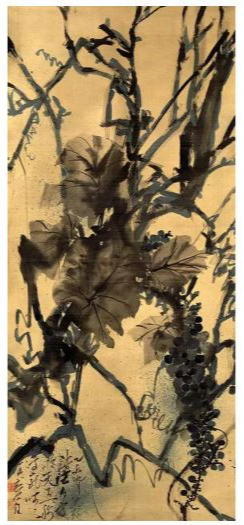

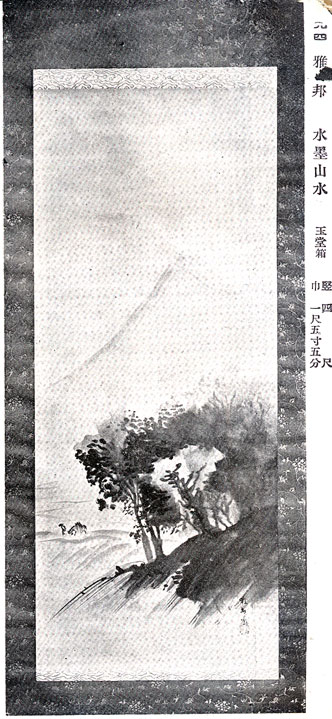

gahou

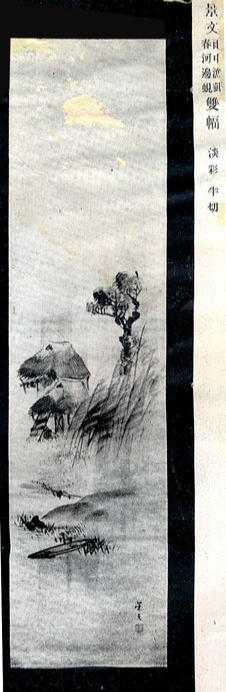

gahou keibun

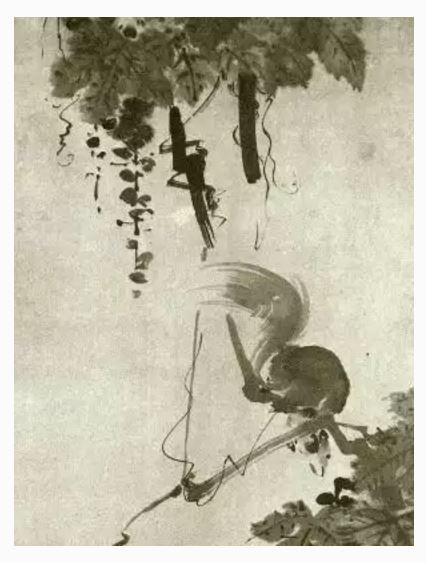

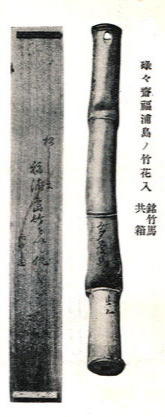

keibun a flower vase made of bamboo

a flower vase made of bamboo